Analyzing Network Data

Last updated on 2025-12-12 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What are networks in the sense that we mean in network analysis?

- What is the structure of a network like and what kind of data can be treated as network data?

- What is the difference between network analysis and network visualization?

- When is it meaningful to perform network anaylsis and network visualization?

Objectives

- Learn the basics of network science and network analysis.

- Learn about the structure of network data.

- Learn to visualize networks.

1. Basics of Network Analysis

What are Network Science and Network Analysis?

Network Science is an interdisciplinary field that studies complex networks, which are structures comprised of interconnected nodes (or vertices) and edges (or links). These networks can represent various real-world systems such as social networks (for example on social media), transportation networks, biological networks, and more. The aim of network science is to understand the topological structure of networks and the relationships that can be discovered within them.

Network Analysis refers to the methods and techniques used to study and evaluate networks. It involves identifying patterns, measuring node importance, analyzing connectivity, and understanding the underlying structure and function of the network.

When and With Which Type of Data is Network Analysis Useful?

Network analysis is particularly useful when the data can be

represented as relationships or interactions between entities. Any type

of data with this quality can be transformed into network data. Network

data is nothing but a tabular dataset with at least two columns: a

source column and a target column. Each of

these columns contains the names of the entities that are connected to

each other in the network. Other columns can contain more information

about the connection between source and

target, including the weight of this connection

(identifying how strong it is) or its type (for example, whether it is a

connection between a human and a work of art, or one between two

humans).

In a visualized network, the sources and targets (usually represented

by dots in the graph) are called nodes, and the lines

connecting them are called edges.

Major Types of Networks

There are many different network types. Familiarity with them helps you decide in the future, when working with your own data, what network type your data can be converted to in order to optimally analyze its different features.

Some important network types include:

1. Directed vs. Undirected Networks

Directed Networks: In these networks, the edges have a direction, indicating a one-way relationship between nodes. For example, in a citation network, if Paper A cites Paper B, the link goes from A to B but not necessarily in the reverse direction.

Undirected Networks: Here, the edges do not have a direction, representing a symmetric relationship. An example would be a friendship network where two people are friends with each other, and the relationship is mutual.

2. Weighted vs. Unweighted Networks

Weighted Networks: In weighted networks, edges have weights assigned to them, indicating the strength or capacity of the relationship. For instance, in a transportation network, the weights could represent distances or travel times.

Unweighted Networks: These networks have edges that are simply present or absent, with no additional information about the strength of connections. An example is a simple social network where the only consideration is whether or not a connection exists.

3. Bipartite Networks

Bipartite networks consist of two distinct sets of nodes, and edges only connect nodes from different sets. An example is a movie recommendation system, where one set consists of users and the other set consists of movies.

4. Homogeneous vs. Heterogeneous Networks

Homogeneous Networks: These networks consist of nodes of the same type. An example is a social network where all nodes represent people.

Heterogeneous Networks: In these networks, nodes can represent different types of entities. For instance, a scientific citation network can include papers, authors, and journals as different types of nodes.

2. Visualizing Network Data

As mentioned above, network data is a specific form of tabular data. For the analyses in this lesson, I have extracted some network data from the website of Wikidata, using the programming language SPARQL. For this lesson, it is not necessary to understand how SPARQL works.

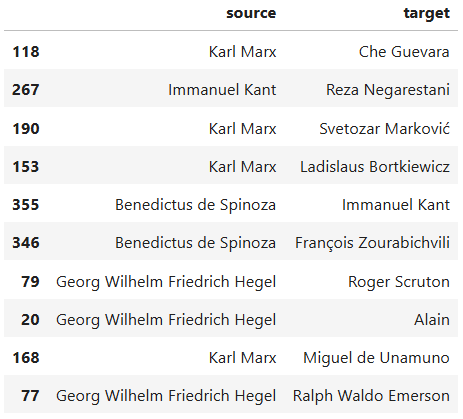

The dataset is stored in a CSV file. It represents a table composed

of two columns: source and target. Both

columns contain names of mostly European personalities. This table was

constructed to represent a directional network, meaning that the

philosophers and thinkers that appear in the source column

have influenced the work of those in the target column.

To construct this dataset, I have searched Wikidata for people whose work has been influenced by Karl Marx, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Immanuel Kant, Benedictus de Spinoza, René Descartes, Plato, or Aristotle, as well as those who have influenced the work of these philosophers. Therefore, these seven personalities make up the most important nodes in the network.

Let’s read the data into Jupyter Notebook, convert it to a Pandas dataframe, and display a sample of that dataframe with ten rows:

PYTHON

import pandas as pd

data_url='https://raw.githubusercontent.com/HERMES-DKZ/python_101_humanities/main/episodes/data/influence_network.csv'

influence_df = pd.read_csv(data_url)

influence_df.sample(10)

Now let’s write some Python code that visualizes the network graph for us:

PYTHON

import networkx as nx

from pyvis.network import Network

# Step 1: Build the NetworkX graph

G = nx.DiGraph()

# Add nodes

all_nodes = set(influence_df['source']).union(set(influence_df['target']))

G.add_nodes_from(all_nodes)

# Add edges

for _, row in influence_df.iterrows():

G.add_edge(row['source'], row['target'])

# Step 2: Create a PyVis network

net = Network(directed=True, height='1000px', width='100%')

# Import the NetworkX graph

net.from_nx(G)

# Step 3: Apply your original visual styling

highlighted = {

'Karl Marx',

'Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel',

'Immanuel Kant',

'Benedictus de Spinoza',

'René Descartes',

'Plato',

'Aristotle'

}

for node in net.nodes:

if node['id'] in highlighted:

node['color'] = 'orangered'

else:

node['color'] = 'slategrey'

for edge in net.edges:

edge['color'] = 'darkseagreen'

edge['arrows'] = 'to'

# Step 4: Save output

net.save_graph("influence_network.html")

print("FINISHED! Network saved as 'influence_network.html'.")

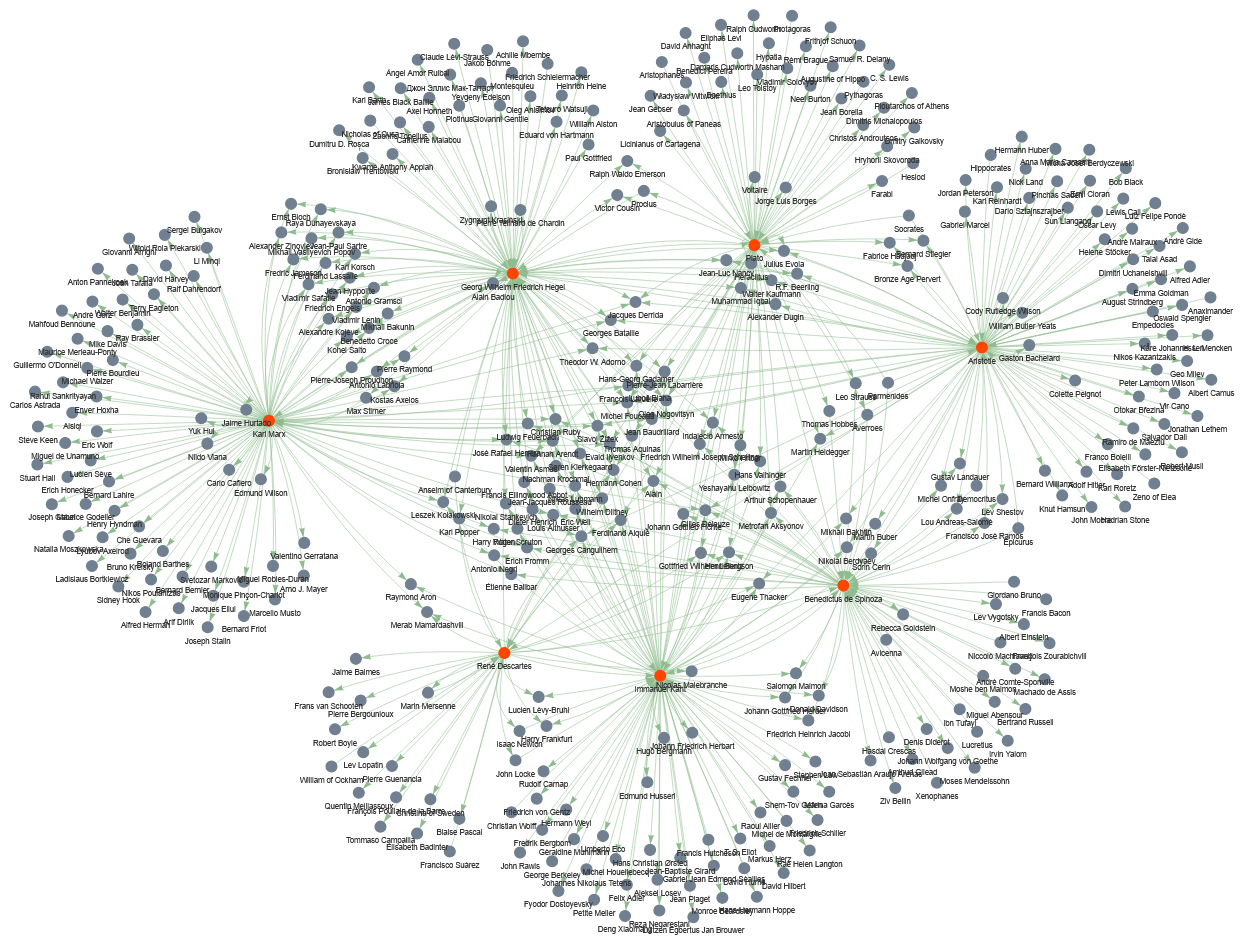

Don’t worry if the network that you have visualized in your code

doesn’t look exactly like the one displayed here. Pyvis

creates interactive network graphs, so that you can pull the nodes

around with the mouse and change their constellation.

Let’s analyze the code line by line

First, let’s look at what is happening at each step:

- Build the

NetworkXgraph: Creates a directed graphG, collects unique node names frominfluence_df, and adds directed edges from source → target. - Create a

PyVisnetwork: Builds an interactive visualization object net (browser-friendly) and imports theNetworkXgraph into it. - Apply visual styling: Colors a chosen set of important nodes (highlighted) differently, sets a color and arrow style for every edge.

- Save output: Writes the interactive HTML file

influence_network.htmland prints a short completion message.

Now, let’s look more deeply into what each code chunk does:

import networkx as nx

from pyvis.network import NetworkImports the NetworkX library under the name

nx — used for building and manipulating graphs. Imports

Network from PyVis, a class for creating

interactive network visualizations that open in a browser.

# Step 1: Build the NetworkX graph

G = nx.DiGraph()Creates an empty directed graph object G (edges have

direction).

# Add nodes

all_nodes = set(influence_df['source']).union(set(influence_df['target']))Collects all unique node names: takes the source column

and target column from influence_df, converts

each to a set, and unions them so each node appears once.

G.add_nodes_from(all_nodes)Adds every element of all_nodes as a node in the graph

G.

# Add edges

for _, row in influence_df.iterrows():

G.add_edge(row['source'], row['target'])Loops over each row of influence_df. For each row, reads

source and target and adds a directed edge from source to

target in G. (_ ignores the row index returned

by iterrows().)

# Step 2: Create a PyVis network

net = Network(directed=True, height='1000px', width='100%')Creates a PyVis Network instance net.

directed=True ensures arrows are shown for direction;

height/width set how big the visualization will appear in the

browser.

# Import the NetworkX graph

net.from_nx(G)Converts the NetworkX graph G into the

PyVis object net, copying nodes and edges so

PyVis can render them interactively.

# Step 3: Apply your original visual styling

highlighted = {

'Karl Marx',

'Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel',

'Immanuel Kant',

'Benedictus de Spinoza',

'René Descartes',

'Plato',

'Aristotle'

}Defines a Python set named highlighted

containing node labels that should receive special visual styling (these

are the seven featured philosophers mentioned earlier).

for node in net.nodes:

if node['id'] in highlighted:

node['color'] = 'orangered'

else:

node['color'] = 'slategrey'Iterates each node in the PyVis representation. In

PyVis, each item in net.nodes is a dictionary

describing one visual node in the interactive network. It contains all

the display attributes PyVis needs to render that node in

the browser. Each dictionary represents one node in your network,

including: - the node’s internal ID (usually the label from the NetworkX

graph) - the text shown next to the node - visual settings such as size,

color, shape, and physics behavior

In each iteration, if the node’s id (its label) is in

highlighted, sets its color to ‘orangered’, otherwise sets

it to ‘slategrey’. This changes node appearance in the HTML output.

for edge in net.edges:

edge['color'] = 'darkseagreen'

edge['arrows'] = 'to'Iterates every edge (each is a dictionary, similar to

net.nodes). Sets the edge color to ‘darkseagreen’ and

ensures an arrowhead points from source to target by setting ‘arrows’ to

‘to’.

# Step 4: Save output

net.save_graph("influence_network.html")Writes the interactive visualization to the file

influence_network.html. Opening that file in a browser

shows the network with the applied styling.

Visualizing network data is very helpful, because it helps you understand the dataset better and decide what insights it can offer you in your research.

Challenge

Study the visualized graph more closely. This is a directional graph of influence in the realm of European philosophy. With a partner, discuss what questions the visualized dataset can answer. These questions guide the further analytic actions that we will undertake in this lesson.

Below are some of the questions that we could answer using this dataset:

- Among the seven highlighted thinkers based on whom the dataset has been curated, which one has been more influential? Which one has had the least among of influence?

- Which thinkers have been influenced by the largest number of the highlighted thinkers?

- How can the influence of the highlighted thinkers be quantitatively measured?

In the following sections, we will answer the questions above using different network analysis techniques.

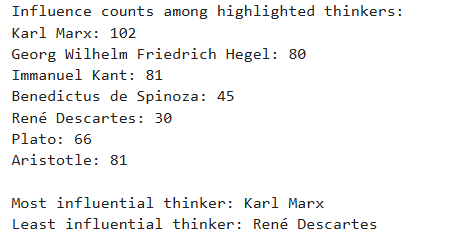

3. Measuring the out-degree

The out-degree of a node is the number of arrows going out from that node. In our influence graph, if a philosopher is connected to many others with arrows pointing from them to others, that means they influenced many people. So:

out-degree = how many people a thinker influenced (according to our dataset).

Let’s write a python code that calculates the out-degree of the highlighted seven thinkers:

PYTHON

# List of highlighted thinkers

highlighted = [

'Karl Marx',

'Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel',

'Immanuel Kant',

'Benedictus de Spinoza',

'René Descartes',

'Plato',

'Aristotle'

]

# Compute integer out-degree safely

influence_counts = {}

for thinker in highlighted:

influence_counts[thinker] = int(G.out_degree(thinker))

# Identify most and least influential

most_influential = max(influence_counts, key=lambda k: influence_counts[k])

least_influential = min(influence_counts, key=lambda k: influence_counts[k])

print("Influence counts among highlighted thinkers:")

for k, v in influence_counts.items():

print(f"{k}: {v}")

print("\nMost influential thinker:", most_influential)

print("Least influential thinker:", least_influential)

Let’s analyze the code line by line

highlighted = [

'Karl Marx',

'Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel',

'Immanuel Kant',

'Benedictus de Spinoza',

'René Descartes',

'Plato',

'Aristotle'

]This line re-defines the highlighted list from the

previous code chunk. The list will be used to loop through these

thinkers later.

influence_counts = {}This line creates an empty dictionary called

influence_counts.

for thinker in highlighted:

influence_counts[thinker] = int(G.out_degree(thinker))These lines create a For loop. The loop goes through the

highlighted list one thinker at a time. During each cycle,

the variable thinker holds one name from the list.

influence_counts[thinker] = int(G.out_degree(thinker))

retrieves the thinker’s out-degree from the graph G.

G.out_degree(thinker) returns how many edges point

outward from that thinker.

int(...) ensures that the result is stored as a plain

integer.

The dictionary influence_counts stores this value under

the thinker’s name.

most_influential = max(influence_counts, key=lambda k: influence_counts[k])This line finds the thinker with the highest out-degree.

max(...) selects the key (the thinker) whose value in the

dictionary is largest.

key=lambda k: influence_counts[k] uses a lambda function

that tells Python to compare items based on their stored influence

number.

A lambda function in Python is a very small, short function that you create without giving it a name. Because it has no name, it is called an anonymous function.

It is used when you need a simple function for a short amount of time

and do not want to write a full function with def.

A simple lambda function looks like this:

lambda x: x + 1This means:

- take an input called x

- return x + 1

So if you used it like this:

f = lambda x: x + 1then f(5) would return 6.

In our code, we have:

key=lambda k: influence_counts[k]This means:

- Python is given a tiny function

- The function takes one input,

k - The function returns `influence_counts[k]```

In other words, when Python tries to find the maximum value in the dictionary, it uses the lambda function to tell it: “Look up the value for each thinker and compare those values.”

least_influential = min(influence_counts, key=lambda k: influence_counts[k])This line works the same way as the previous one, but uses

min(...) to find the smallest out-degree. The result is the

thinker who influenced the fewest people in the dataset.

Finally, the last code lines implement functions that you have already learned in the previoius episodes.

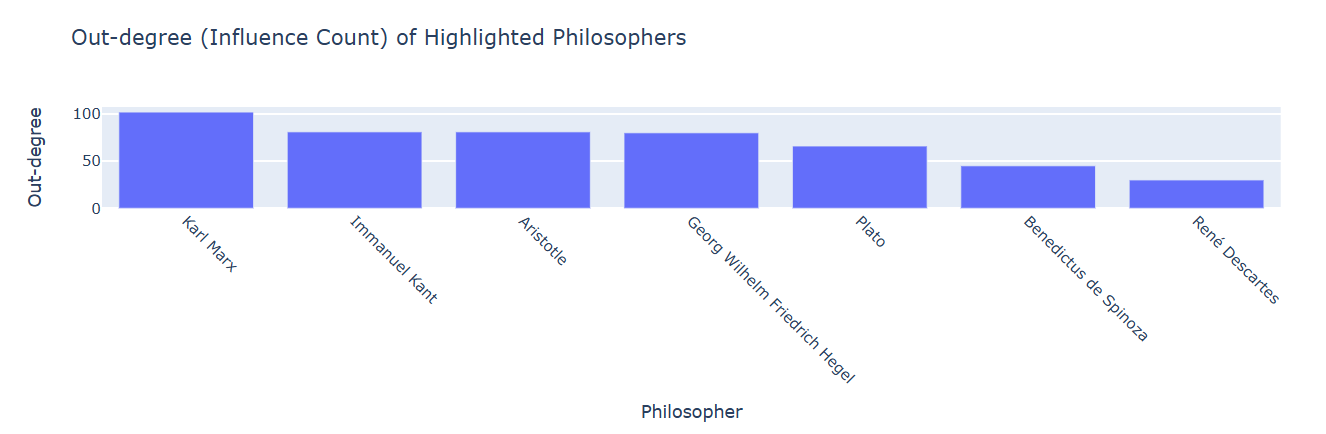

So far, we know that Karl Marx has been the most influential among the highlighted personalities in our dataset, whereas the least influential person has been René Descartes. Let’s draw a bar chart to better understand the out-degrees of the seven selected nodes, which gives us a measure of how influential they have been in the world of philosophy and literature.

PYTHON

import plotly.express as px

# Sort philosophers by out-degree (highest → lowest)

sorted_items = sorted(influence_counts.items(), key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True)

# Unpack the sorted items back into two lists

philosophers = [item[0] for item in sorted_items]

out_degrees = [item[1] for item in sorted_items]

# Create bar plot

fig = px.bar(

x=philosophers,

y=out_degrees,

labels={'x': 'Philosopher', 'y': 'Out-degree'},

title='Out-degree (Influence Count) of Highlighted Philosophers'

)

fig.show()

In the above code, only the few first lines merit a brief explanation.

Let’s analyze a few code lines

sorted_items = sorted(influence_counts.items(), key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True)influence_counts.items() produces all key–value pairs

from the dictionary. Each item looks like: (‘Plato’, 9) or (‘Aristotle’,

6).

sorted(..., key=lambda x: x[1], reverse=True) Sorts

those key–value pairs based on the value (the out-degree).

x represents one pair, such as (‘Plato’, 9).

x[1] selects the second part of the pair, the

out-degree.

reverse=True makes the list sorted from highest to

lowest.

The result, stored in sorted_items, is a list of tuples

ordered by out-degree.

philosophers = [item[0] for item in sorted_items]This creates a new list containing only the names of the

philosophers, in the sorted order. item[0] means “take the

first part of each tuple,” which is the philosopher’s name.

out_degrees = [item[1] for item in sorted_items]This creates another list containing only the out-degree numbers, in

the same sorted order. item[1] means “take the second part

of each tuple,” which is the out-degree.

4. Measuring the in-degree

In the previous section, we measured the out-degrees. In this one, we want to measure the in-degrees to see which thinkers have been influenced by the largest number of the highlighted thinkers, which translates into: which nodes have the highest number of arrows pointing at them. We count, for each node, how many of its incoming edges come from the highlighted thinkers.

Let’s write a Python code that performs the in-degree count for us:

PYTHON

# Step 1: Create a dictionary to count influences from highlighted thinkers

influence_count = {node: 0 for node in G.nodes}

# Step 2: Count how many highlighted thinkers influence each node

for target in G.nodes:

predecessors = set(G.predecessors(target)) # thinkers influencing this target

influence_count[target] = len(predecessors.intersection(highlighted))

# Step 3: Find the maximum count

max_influence = max(influence_count.values())

# Step 4: Find the non-highlighted thinkers influenced by the maximum number of highlighted thinkers

most_influenced_thinkers = [

node for node, count in influence_count.items()

if count == max_influence and node not in highlighted

]

print("Thinkers influenced by the maximum number of highlighted thinkers:", most_influenced_thinkers)

print("Number of highlighted thinkers influencing them:", max_influence)

Let’s analyze the code line by line

influence_count = {node: 0 for node in G.nodes}G.nodes gives a list of all thinkers (nodes) in the

network.

{node: 0 for node in G.nodes} is a dictionary

comprehension. It creates a dictionary where each thinker starts with a

count of 0, meaning initially we assume no highlighted thinkers

influence them.

for target in G.nodes:

predecessors = set(G.predecessors(target)) # thinkers influencing this target

influence_count[target] = len(predecessors.intersection(highlighted))for target in G.nodes: loops over every thinker in the

network.

G.predecessors(target) gives a list of thinkers who have

an arrow pointing to this thinker — in other words, thinkers who

influenced them.

set(predecessors) converts the list of influencers into

a set for easy comparison.

predecessors.intersection(highlighted) finds which of

the influencers are in our highlighted thinkers set.

len(...) counts how many highlighted thinkers influence

this node.

influence_count[target] = ... updates the dictionary

with this number.

max_influence = max(influence_count.values())influence_count.values() gives all the counts of

highlighted thinkers for each node.

max(...) finds the largest number, i.e., the highest

number of highlighted thinkers influencing a single thinker.

most_influenced_thinkers = [

node for node, count in influence_count.items()

if count == max_influence and node not in highlighted

]The list comprehension

[node for node, count in ... if count == max_influence and node not in highlighted]

creates a list of thinkers whose count equals the maximum. It also makes

sure that the nodes in this list, whose in-degrees are being measured,

do not belong to the highlighted list.

The thinkers in the list most_influenced_thinkers are

those influenced by the highest number of highlighted thinkers.

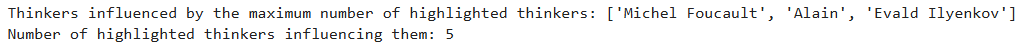

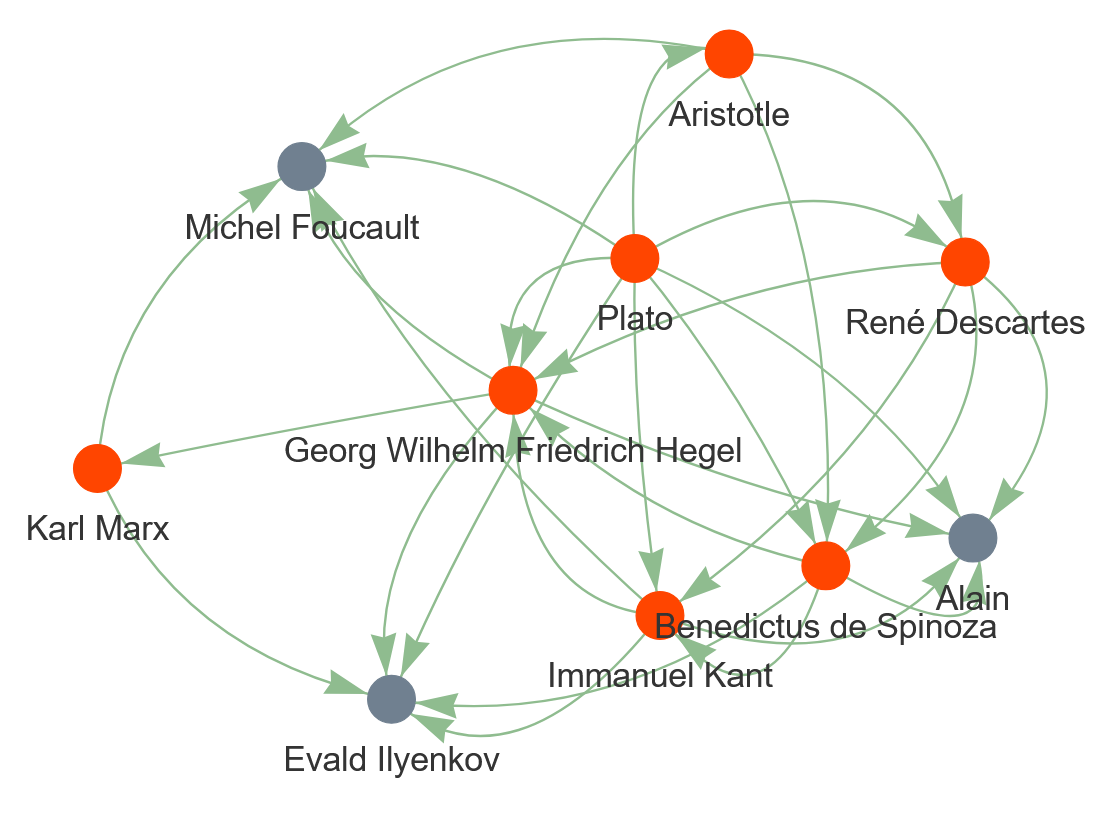

Wonderful! We now know that Michel Foucault, Alain, and Evald Ilyenkov have taken the greatest influence from the highlighted thinkers. Let’s now create a filtered network dataset, consisting only of these three nodes and the seven highlighted thinkers, and visualize it. This visualization should give us a better understanding of European philosophy’s landscape concerning the seven highlighted thinkers:

PYTHON

import pandas as pd

import networkx as nx

from pyvis.network import Network

# Combine nodes to include in the smaller network

nodes_to_include = highlighted.union(most_influenced_thinkers)

# Step 1: Build the filtered NetworkX graph

G_filtered = nx.DiGraph()

# Add only the relevant nodes

G_filtered.add_nodes_from(nodes_to_include)

# Add edges only if both source and target are in nodes_to_include

for _, row in influence_df.iterrows():

if row['source'] in nodes_to_include and row['target'] in nodes_to_include:

G_filtered.add_edge(row['source'], row['target'])

# Step 2: Create a PyVis network

net = Network(directed=True, height='1000px', width='100%')

# Import the filtered NetworkX graph

net.from_nx(G_filtered)

# Step 3: Apply the same visual styling

for node in net.nodes:

if node['id'] in highlighted:

node['color'] = 'orangered'

else:

node['color'] = 'slategrey'

for edge in net.edges:

edge['color'] = 'darkseagreen'

edge['arrows'] = 'to'

# Step 4: Save the filtered network

net.save_graph("filtered_influence_network.html")

print("FINISHED! Filtered network saved as 'filtered_influence_network.html'.")

With a peer, study the visualized graph carefully and discuss what information it provides about European philosophy.

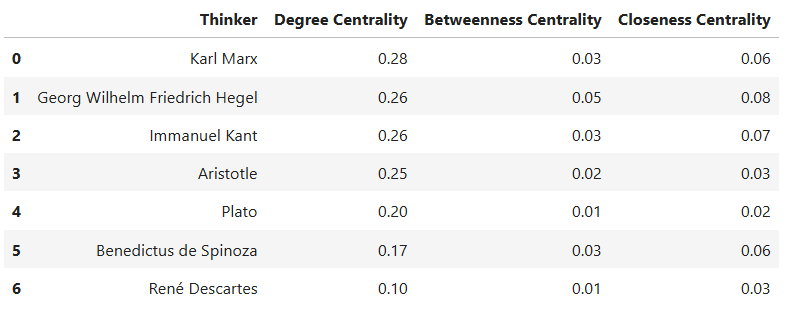

5. Measuring centrality degrees

Finally in this episode, let’s answer the third question we stated above: How can the influence of the highlighted thinkers be quantitatively measured? To do so, we can measure three so-called centrality degrees for the nodes in the highlighted list. These are:

- Degree Centrality

- Betweenness Centrality

- Closeness Centrality

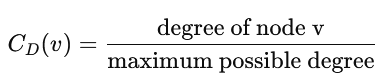

Degree Centrality

Definition:

- Measures the number of direct connections a node has to other nodes.

- In a directed graph, degree centrality usually counts both incoming and outgoing edges unless specifically split into in-degree and out-degree centrality.

Why we measure it:

- It shows how “connected” a node is in the network.

- In a social or influence network, a thinker with a high degree centrality either influences many thinkers (high out-degree) or is influenced by many thinkers (high in-degree).

- It is a simple and intuitive measure of a node’s importance in terms of direct connections.

Unit and Range:

- Normalized unitless number that ranges from 0 to 1:

- 0 means no connections, 1 means connected to all other nodes in the network.

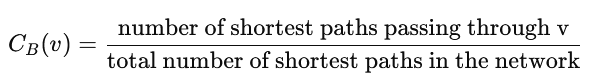

Betweenness Centrality

Definition:

- Measures how often a node lies on the shortest paths between other pairs of nodes.

- A node with high betweenness acts as a “bridge” or bottleneck connecting different parts of the network.

Why we measure it:

- Identifies thinkers who are key intermediaries.

- Even if a thinker is not highly connected (low degree), they may control the flow of influence in the network if many shortest paths pass through them.

Unit and Range:

- Normalized unitless number that ranges from 0 to 1:

- 0 means the node is never on a shortest path between any two other nodes.

- 1 means the node is on all shortest paths (rare in real networks).

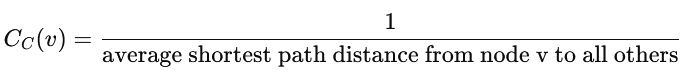

Closeness Centrality

Definition:

- Measures how close a node is to all other nodes in the network, based on the shortest paths.

- High closeness means a node can quickly interact with (or influence) all other nodes.

Why we measure it:

- Shows which thinkers are “centrally located” in the network.

- A thinker with high closeness can reach many others efficiently, making them influential even without high degree or betweenness.

Unit and Range:

- Normalized unitless number that ranges from 0 to 1:

- 0 means the node is very far from others (or disconnected).

- 1 means the node is as close as possible to all others (rare).

At this stage, you should be at a point where you can understand the following code without any explanation. Congratulations! You’re becoming a profi in Python programming!

Now that you know what information these centrality degrees reveal, let’s measure them for the nodes in the list of highlighted thinkers.

PYTHON

import pandas as pd

# Step 1: Calculate centralities

degree_centrality = nx.degree_centrality(G)

betweenness_centrality = nx.betweenness_centrality(G)

closeness_centrality = nx.closeness_centrality(G)

# Step 2: Collect centralities only for highlighted thinkers

data = []

for node in highlighted:

data.append({

'Thinker': node,

'Degree Centrality': round (degree_centrality[node], 2),

'Betweenness Centrality': round (betweenness_centrality[node], 2),

'Closeness Centrality': round (closeness_centrality[node], 2)

})

# Step 3: Create a pandas DataFrame

centrality_df = pd.DataFrame(data)

# Step 4: Sort by Degree Centrality (optional)

centrality_df = centrality_df.sort_values(by='Degree Centrality', ascending=False).reset_index(drop=True)

centrality_df

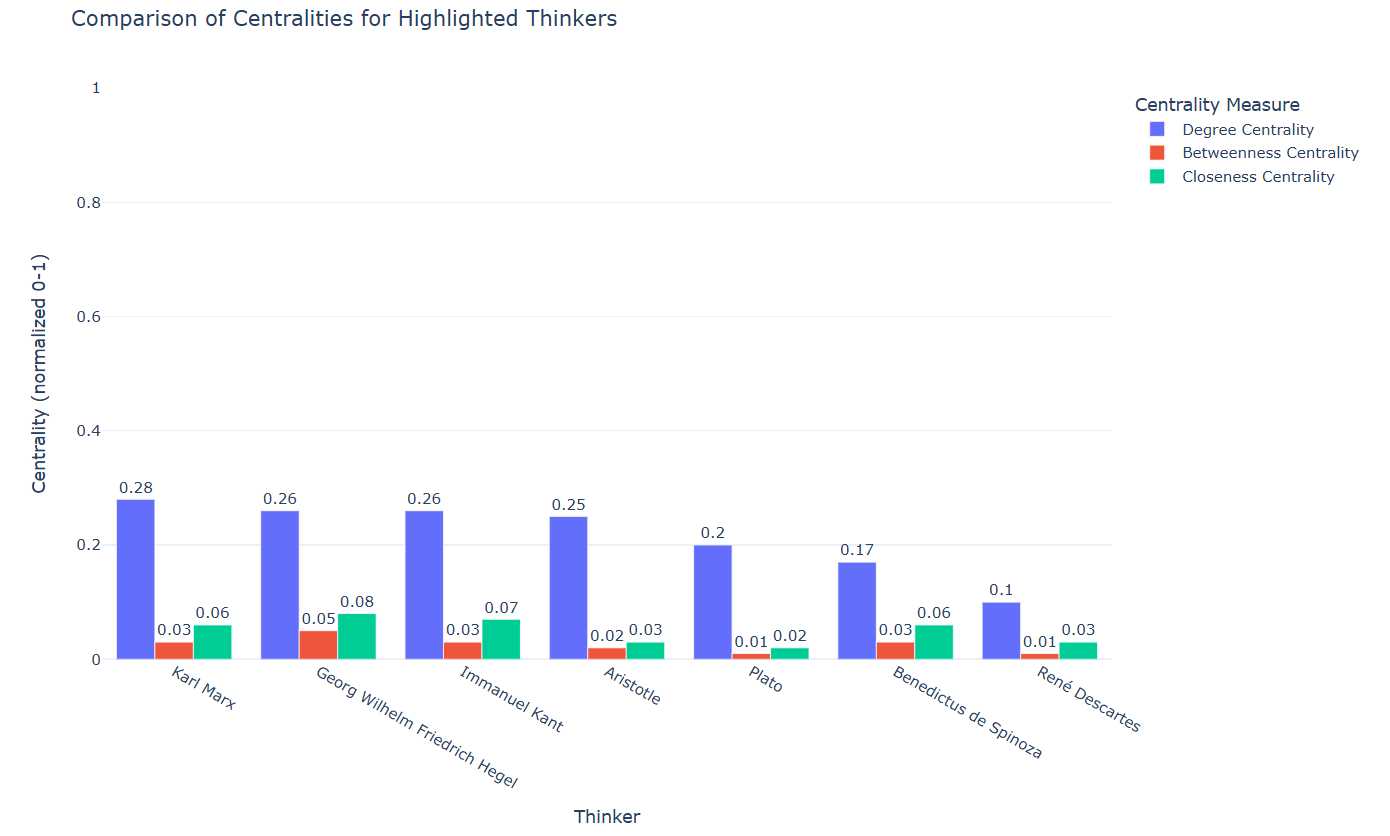

To develop a better understanding of the degree centralities in the dataframe, let’s visualize them in a stacked bar chart:

PYTHON

# Step 1: Transform the DataFrame to long format

centrality_long = centrality_df.melt(

id_vars='Thinker',

value_vars=['Degree Centrality', 'Betweenness Centrality', 'Closeness Centrality'],

var_name='Centrality',

value_name='Value'

)

# Step 2: Create a grouped bar chart with text above the bars

fig = px.bar(

centrality_long,

x='Thinker',

y='Value',

color='Centrality',

barmode='group',

text='Value', # Show numeric values

title='Comparison of Centralities for Highlighted Thinkers',

height=700

)

# Step 3: Ensure all text values are horizontally above the bars

fig.update_traces(textposition='outside') # Forces all values above bars

# Step 4: Customize layout

fig.update_layout(

xaxis_title='Thinker',

yaxis_title='Centrality (normalized 0-1)',

legend_title='Centrality Measure',

yaxis=dict(range=[0, 1]),

template='plotly_white'

)

# Step 5: Show figure

fig.show()

Now that you know what each centrality degree means and you have the measures and graphs regarding the centrality degrees of the seven highlighted thinkers in the network data, discuss with a partner:

- What do these measures mean for the seven selected thinkers?

- Which thinker among the highlighted ones has the highest number of connections?

- Which thinker has most effectively served as a bridge between other thinkers in the network data?

- Which thinker has likely most influenced or been influenced by others in the network?

- Understand the use cases of network analysis.

- Visualize networks using the Python library Pyvis.